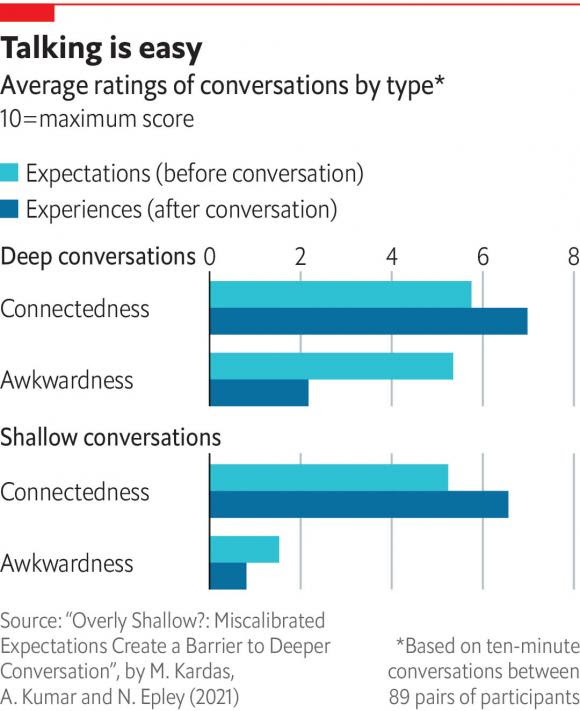

Deep impact: it’s time to ditch the small talk Imagine waiting in a queue or for a bus, when a stranger sidles up to you and genially asks: “What is your life’s greatest regret?” If that thought fills you with horror, read on. According to research in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, people secretly crave deeper conversations with strangers. Imagine waiting in a queue or for a bus, when a stranger sidles up to you and genially asks: “What is your life’s greatest regret?” If that thought fills you with horror, read on. According to research in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, people secretly crave deeper conversations with strangers.In experiments with 1,800 people, pairs of strangers were prompted to discuss topics either shallow (“Seen anything good on telly lately?”) or deep (“When was the last time you cried?”). Before-and-after surveys revealed that all conversations, but especially deeper ones, were less awkward than people expected. They were also more enjoyable and aroused a greater sense of connectedness than stock chit-chat. Psychologists say people underestimate how interested in them strangers are, and should delve deeper than the usual natter about football or the weather. So the next time you break the ice with a stranger, consider using a sledgehammer instead of a pick.  |

Deep impact: it’s time to ditch the small talk PHOTO: GETTY IMAGES Imagine waiting in a queue or for a bus, when a stranger sidles up to you and genially asks: “What is your life’s greatest regret?” If that thought fills you with horror, read on. According to research in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, people secretly crave deeper conversations with strangers. In experiments with 1,800 people, pairs of strangers were prompted to discuss topics either shallow (“Seen anything good on telly lately?”) or deep (“When was the last time you cried?”). Before-and-after surveys revealed that all conversations, but especially deeper ones, were less awkward than people expected. They were also more enjoyable and aroused a greater sense of connectedness than stock chit-chat. Psychologists say people underestimate how interested in them strangers are, and should delve deeper than the usual natter about football or the weather. So the next time you break the ice with a stranger, consider using a sledgehammer instead of a pick.

The Economist Espresso via e-mail for Monday October 4th – greg.rafferty@gmail.com – Gmail

Iris Murdoch

Losing native languages is painful. But they can be recovered In “Memory Speaks”, Julie Sedivy explores both experiences

Losing native languages is painful. But they can be recovered | The Economist

Losing native languages is painful. But they can be recovered

In “Memory Speaks”, Julie Sedivy explores both experiences

Jan 29th 2022

Memory is unfaithful. As William James, a pioneering psychologist of the 19th and early 20th centuries, observed: “There is no such thing as mental retention, the persistence of an idea from month to month or year to year in some mental pigeonhole from which it can be drawn when wanted. What persists is a tendency to connection.”

Julie Sedivy quotes James in a poignant context in her new book “Memory Speaks”. She was whisked from Czechoslovakia with her family at the age of two, settling eventually in Montreal. In her new home she became proficient in French and English, and later became a scholar in the psychology of language. But she nearly lost her first language, Czech, before returning to it in adulthood. Her book is at once an eloquent memoir, a wide-ranging commentary on cultural diversity and an expert distillation of the research on language learning, loss and recovery.

Her story is sadly typical. Youngsters use the child’s plastic brain to learn the language of an adoptive country with what often seems astonishing speed. Before long it seems to promise acceptance and opportunity, while their parents’ language becomes irrelevant or embarrassing, something used only by old people from a faraway place. The parents’ questions in their home language are answered impatiently in the new one, the children coming to regard their elders as out-of-touch simpletons who struggle to complete basic tasks.

For their part, meanwhile, the parents cannot lead the subtle, difficult conversations that guide their offspring as they grow. As the children’s heritage language atrophies, the two generations find it harder and harder to talk about anything at all.

Children often yearn desperately to fit in. Often this can mean not only learning the new language, but avoiding putting off potential friends with the old. Children, alas, can also be little bigots. At the age of five, researchers have found, they already express a preference for hypothetical playmates of the same race as them. They also prefer friends who speak only their language over those who speak a second one as well.

In theory, keeping a language robust once uprooted from its native environment is possible. But that requires the continuance of a rich and varied input throughout a child’s development—not just from parents, but through activities, experiences, books and media. These are often not available in countries of arrival. Parents are themselves pressed to speak in the new language to their children, despite evidence that their ungrammatical and halting efforts are not much help.

But a dimming language may not be as profoundly lost as speakers fear when, as adults, they visit elderly relatives or their home countries and can barely produce a sentence. Though the language may not be as retrievable as it once was, with time and exposure it can be relearned far faster than if starting from scratch.

This depends, naturally, on the length of time someone spent speaking their first language as a child. Those who are older when they emigrate may keep their languages without great effort (though none is entirely safe from attrition). Those who leave at younger ages may find their grasp of grammar weakening, but will still have a large dormant vocabulary that can be reawakened, and are likely to speak with a near-native accent when they do. Most remarkably, even children adopted across international borders in the first years of life, before they can properly speak themselves, show enhanced ability to learn sounds that are native to their birth-country languages, after not hearing them for most of their lives.

Many bilingual people report feeling that they have different personalities in their different languages; overwhelmingly they say that their first language is the one most imbued with emotion. It is scarcely surprising that losing a mother-tongue leaves behind an ache like that of a phantom limb.

The official pressure on newcomers to abandon their old languages used to be much worse. Today, some democracies with long histories of immigration try to be more accommodating. Schools may bolster pupils’ multilingualism by, for example, getting them to write stories or poems in their home languages and explain them to the class. Such symbolic support shows the children that they are not considered divided souls or outsiders, but full members of their new communities—and ones blessed with a precious gift.

How to Talk to StrangersThe health benefits are clear. The political benefits are newly relevant.By James Hamblin

How to Talk to Strangers IRL – The Atlantic

How to Talk to Strangers

The health benefits are clear. The political benefits are newly relevant.By James Hamblin

AUGUST 25, 2016SHARE

Next time you enter an elevator, walk in and keep facing the back wall. If you stay that way, in my experience, people will laugh or ask if you’re okay. (That’s an opportunity, if you want, to say you would love for someone to define “okay.”)

Standing this way breaks unstated rules of how we’re supposed to behave in elevators. Detaching from expectations gives people an excuse to talk, to acknowledge one another’s humanity. Absent a break in the order, the expectation is silence.

(Of course, you can make a quick joke—my favorite is, if the elevator is stopping frequently, “What is this, the local train?”—and expect a modicum of laughter. But even if the joke goes over well, the rule seems to be that you can’t say it more than once in the same ride.)

The celebrated Canadian sociologist Erving Goffman saw elevators as microcosms of society. Described by the Times Literary Supplement as “a public private eye,” Goffman covertly studied people as they rode in elevators in 1963. He noted that the rule upon entering seemed to be to give some brief visual notice of other passengers, and then to withdraw attention, not making eye contact again at any point. (Though 35 percent of people added one or two glances to the initial look.)

Goffman called this civil inattention. That is, we act civilized toward one another—not harming anyone or blocking their paths or shouting in an enclosed space—but also not attentive. This goes on today, wherever people might be described as alone together.

“That’s the principle that’s operational when people aren’t talking to each other on the subway,” Kio Stark, the author of the forthcoming book When Strangers Meet, explained to me. “You can pretend you’re there by yourself.”

And this is good and necessary at times, especially in a city as bereft of solitude as New York. But it can be overdone. As Stark argues from the top of the book, “This if nothing else: Talking to strangers is good for you.”

Her work appealed to me because I’ve suggested as much in a mediocre piece called “Always Talk to Strangers.” That was based on a study that found that people who considered their neighbors to be friendly and trustworthy were less likely to have heart attacks. Other public-health research has shown improved moods among commuters who chat on the subway, and happiness and creativity among people who talk to strangers.

Kio Stark always has and does. She was born in a New York family and doesn’t think it’s rare. Her reasons are many, but among the most compelling is essentially boredom. She writes that a stranger-encounter is “an exquisite interruption” to whatever expectations you had about your day. Go to work, and you know who you’ll see. Hang out with friends, and you know what to expect. But engage with a stranger, and at least something interesting might happen.

“It’s not only about novelty,” she added when we spoke. “It’s about feeling connected to my block, my neighborhood.”

At a grander scale, in an increasingly polarized society, it can require concerted effort to break out of sociocultural strata and online algorithms that are constantly pairing us with like-minded people. (Don’t know anyone who’s voting for Trump? That’s on you.)

Beyond the promise of a unique and enlightening experience, there is also the little jolt of breaking a rule. Of course, not a rule rule, like harassment or assault, but an unstated social rule. It’s up to us to know when and how to break those rules in ways that don’t unduly offend or put other people out. That’s the hard part. So she suggests exercises to start. Figure out what makes you uncomfortable, and target ways to get over those. A good one for most people is just to do an exercise where you walk around your neighborhood and just say “hi” to everyone you see.

Once you’ve mastered that, try having an actual interaction (not necessarily a conversation). That usually works well by doing what Stark calls “triangulation.” That’s sociology-speak for remarking on something external to both you and the stranger—something you’re both experiencing or observing. Like the weather, but less boring. Commenting on a shared experience tends to be less confrontational than making a remark about the other person directly, however flattering (read: creepy).

Once you’ve mastered saying hi and triangulating, Stark suggests advanced strategies like asking people profound existential questions, or getting lost in a neighborhood where you have to genuinely ask people for directions. And, before doing that, embrace the sensation of being “the stranger” who doesn’t belong. She describes that as “emotionally risky.”

So I didn’t try that one. But I did attempt some others, and you can watch them here in today’s captivating episode of If Our Bodies Could Talk.https://www.theatlantic.com/video/iframe/497309If Our Bodies Could Talk

One fun behind-the-scenes fact is that I met a guy named Enrique in the park, and he was there practicing on his brand new, red guitar-kelele. (It’s barely larger than a ukelele, and has six strings like a guitar.) We chatted for a while, and I asked if I could play it. He kindly agreed. I played for a long time. I played all of “Stairway to Heaven.” I was sort of testing the waters of his politeness, which were apparently boundless. Anyway, we had to cut this footage because our legal team told us that someone already owns the performance rights to “Stairway to Heaven.”

British Writer Pens The Best Description Of Trump I’ve Read

British Writer Pens The Best Description Of Trump I’ve Read – London Daily

British Writer Pens The Best Description Of Trump I’ve Read

Nate White“Why do some British people not like Donald Trump?” Nate White, an articulate and witty writer from England wrote the following response:A few things spring to mind. Trump lacks certain qualities which the British traditionally esteem. For instance, he has no class, no charm, no coolness, no credibility, no compassion, no wit, no warmth, no wisdom, no subtlety, no sensitivity, no self-awareness, no humility, no honour and no grace – all qualities, funnily enough, with which his predecessor Mr. Obama was generously blessed. So for us, the stark contrast does rather throw Trump’s limitations into embarrassingly sharp relief.

Plus, we like a laugh. And while Trump may be laughable, he has never once said anything wry, witty or even faintly amusing – not once, ever. I don’t say that rhetorically, I mean it quite literally: not once, not ever. And that fact is particularly disturbing to the British sensibility – for us, to lack humour is almost inhuman. But with Trump, it’s a fact. He doesn’t even seem to understand what a joke is – his idea of a joke is a crass comment, an illiterate insult, a casual act of cruelty.

Trump is a troll. And like all trolls, he is never funny and he never laughs; he only crows or jeers. And scarily, he doesn’t just talk in crude, witless insults – he actually thinks in them. His mind is a simple bot-like algorithm of petty prejudices and knee-jerk nastiness.

There is never any under-layer of irony, complexity, nuance or depth. It’s all surface. Some Americans might see this as refreshingly upfront. Well, we don’t. We see it as having no inner world, no soul. And in Britain we traditionally side with David, not Goliath. All our heroes are plucky underdogs: Robin Hood, Dick Whittington, Oliver Twist. Trump is neither plucky, nor an underdog. He is the exact opposite of that. He’s not even a spoiled rich-boy, or a greedy fat-cat. He’s more a fat white slug. A Jabba the Hutt of privilege.

And worse, he is that most unforgivable of all things to the British: a bully. That is, except when he is among bullies; then he suddenly transforms into a snivelling sidekick instead. There are unspoken rules to this stuff – the Queensberry rules of basic decency – and he breaks them all. He punches downwards – which a gentleman should, would, could never do – and every blow he aims is below the belt. He particularly likes to kick the vulnerable or voiceless – and he kicks them when they are down.

So the fact that a significant minority – perhaps a third – of Americans look at what he does, listen to what he says, and then think ‘Yeah, he seems like my kind of guy’ is a matter of some confusion and no little distress to British people, given that:

• Americans are supposed to be nicer than us, and mostly are.

• You don’t need a particularly keen eye for detail to spot a few flaws in the man.

This last point is what especially confuses and dismays British people, and many other people too; his faults seem pretty bloody hard to miss. After all, it’s impossible to read a single tweet, or hear him speak a sentence or two, without staring deep into the abyss. He turns being artless into an art form; he is a Picasso of pettiness; a Shakespeare of shit. His faults are fractal: even his flaws have flaws, and so on ad infinitum. God knows there have always been stupid people in the world, and plenty of nasty people too. But rarely has stupidity been so nasty, or nastiness so stupid. He makes Nixon look trustworthy and George W look smart. In fact, if Frankenstein decided to make a monster assembled entirely from human flaws – he would make a Trump.

And a remorseful Doctor Frankenstein would clutch out big clumpfuls of hair and scream in anguish: ‘My God… what… have… I… created?’ If being a twat was a TV show, Trump would be the boxed set.

Travels With Boji: Istanbul’s Commuter Dog

Travels With Boji: Istanbul’s Commuter Dog – The Atlantic

Boji, a street dog living in Istanbul, Turkey, has become a popular sight on the city’s subways, ferries, trams, and buses. Chris McGrath, a photographer with Getty Images, recently joined Boji as he made his rounds, during which he can travel as much as 30 kilometers a day. “Since noticing the dog’s movements,” McGrath says, “Istanbul Municipality officials began tracking his commutes via a microchip and a phone app. Most days he will pass through at least 29 metro stations and take at least two ferry rides. He has learned how and where to get on and off the trains and ferries.”HINTS: View this page full screen. Skip to the next and previous photo by typing j/k or ←/→.

Boji, an Istanbul street dog, rides a subway train in Istanbul, Turkey, on October 21, 2021. #Chris McGrath / Getty

Boji, an Istanbul street dog, rides a subway train in Istanbul, Turkey, on October 21, 2021. #Chris McGrath / Getty Boji rides Kadiköy’s historic tram on October 21, 2021. #Chris McGrath / Getty

Boji rides Kadiköy’s historic tram on October 21, 2021. #Chris McGrath / Getty Boji boards a ferry to Beşiktaş on October 21, 2021, in Istanbul. #Chris McGrath / Getty

Boji boards a ferry to Beşiktaş on October 21, 2021, in Istanbul. #Chris McGrath / Getty People watch as Boji rides a ferry on October 21, 2021. #Chris McGrath / Getty

People watch as Boji rides a ferry on October 21, 2021. #Chris McGrath / Getty Time for a rest: Boji finds a seat aboard a ferry to Beşiktaş on October 21, 2021. #Chris McGrath / Getty

Time for a rest: Boji finds a seat aboard a ferry to Beşiktaş on October 21, 2021. #Chris McGrath / Getty Boji naps on the ferry to Beşiktaş on October 21, 2021. #Chris McGrath / Getty

Boji naps on the ferry to Beşiktaş on October 21, 2021. #Chris McGrath / Getty Boji trots through a subway station to catch a train on October 21, 2021, in Istanbul. #Chris McGrath / Getty

Boji trots through a subway station to catch a train on October 21, 2021, in Istanbul. #Chris McGrath / Getty Boji passes through subway-station turnstiles on October 21, 2021. #Chris McGrath / Getty

Boji passes through subway-station turnstiles on October 21, 2021. #Chris McGrath / Getty Boji stands on a subway platform waiting for a train to arrive on October 21, 2021. #Chris McGrath / Getty

Boji stands on a subway platform waiting for a train to arrive on October 21, 2021. #Chris McGrath / Getty Boji allows other commuters to disembark while waiting to board a subway train on October 21, 2021. #Chris McGrath / Getty

Boji allows other commuters to disembark while waiting to board a subway train on October 21, 2021. #Chris McGrath / Getty Boji takes a drink from bowls provided for stray animals inside the Kadiköy subway station, before catching a train on October 21, 2021. #Chris McGrath / Getty

Boji takes a drink from bowls provided for stray animals inside the Kadiköy subway station, before catching a train on October 21, 2021. #Chris McGrath / Getty Boji rides Kadiköy’s historic tram on October 21, 2021, in Istanbul. #Chris McGrath / Getty

Boji rides Kadiköy’s historic tram on October 21, 2021, in Istanbul. #Chris McGrath / Getty Boji rounds a fence corner at the Kadiköy ferry station on October 21, 2021. #Chris McGrath / Getty

Boji rounds a fence corner at the Kadiköy ferry station on October 21, 2021. #Chris McGrath / Getty Boji rests in the sun on a ferry to Beşiktaş on October 21, 2021. #Chris McGrath / Getty

Boji rests in the sun on a ferry to Beşiktaş on October 21, 2021. #Chris McGrath / Getty In the passageways of a subway station, Boji runs to catch a train on October 21, 2021. #Chris McGrath / Getty

In the passageways of a subway station, Boji runs to catch a train on October 21, 2021. #Chris McGrath / Getty Boji chases an arriving subway train on October 21, 2021. #Chris McGrath / Getty

Boji chases an arriving subway train on October 21, 2021. #Chris McGrath / Getty A man pats Boji while riding a subway train on October 21, 2021. #Chris McGrath / Getty

A man pats Boji while riding a subway train on October 21, 2021. #Chris McGrath / Getty Boji is groomed and given a medical check by staff at an Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality animal shelter on October 8, 2021. #

Boji is groomed and given a medical check by staff at an Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality animal shelter on October 8, 2021. #

The Hidden Costs of Living Alone In ways both large and small, American society still assumes that the default adult has a partner and that the default household contains multiple people. By Joe Pinsker

Living Alone in the U.S. Is Harder Than It Should Be – The Atlantic

The Hidden Costs of Living Alone

In ways both large and small, American society still assumes that the default adult has a partner and that the default household contains multiple people.By Joe Pinsker

OCTOBER 20, 2021SHARE

If you were to look under the roofs of American homes at random, it wouldn’t take long to find someone who lives alone. By the Census Bureau’s latest count, there are about 36 million solo dwellers, and together they make up 28 percent of U.S. households.

Even though this percentage has been climbing steadily for decades, these people are still living in a society that is tilted against them. In the domains of work, housing, shopping, and health care, much of American life is a little—and in some cases, a lot—easier if you have a partner or live with family members or housemates. The number of people who are inconvenienced by that fact grows every year.

Those who live alone, to be clear, are not lonely and miserable. Research indicates that, young or old, single people are more social than their partnered peers. Bella DePaulo, the author of How We Live Now: Redefining Home and Family in the 21st Century, reeled off to me some of the pleasures of having your own space: “the privacy, the freedom to arrange your life and your space just the way you want it—you get to decide when to sleep, when to get up, what you eat, when you eat, what you watch on Netflix, how you set the thermostat.”

The difficulties of living alone tend to lie more on a societal level, outside the realm of personal decision making. For one thing, having a partner makes big and small expenditures much more affordable, whether it’s a down payment on a house, rent, day care, utility bills, or other overhead costs of daily life. One recent study estimated that, for a couple, living separately is about 28 percent more expensive than living together.

These efficiencies are an inherent feature of sharing costs with other people, but the barriers to living alone, for those who want to, would be much lower if housing (and health care, and education) weren’t so expensive. Moreover, the types of housing that are most commonly available for one person typically privilege privacy over togetherness, but the two don’t need to be mutually exclusive. DePaulo has studied communities where single residents have their own spaces, but also plentiful shared areas with “the possibility of running into other people.” If you need to, say, move heavy furniture or get a ride somewhere in an emergency, your neighbors are easy to reach. More such options would make solo life easier.

Many who live by themselves are effectively penalized at work too. “Lots of people I interviewed complained that their managers presumed they had extra time to stay at the office or take on extra projects because they don’t have family at home,” Eric Klinenberg, the author of the 2012 book Going Solo: The Extraordinary Rise and Surprising Appeal of Living Alone and a sociologist at NYU, told me. “Some said that they were not compensated fairly either, because managers gave raises to people based on the impression that they had more expenses, for child care and so on.”

And if many workers who live alone end up making less money, as consumers they face less favorable pricing options than other shoppers. Buying larger quantities of food at the grocery store is usually cheaper, but as DePaulo pointed out, people who live alone might not get through perishable items quickly enough. (She wishes more stores would let people buy only as much of something as they please, instead of locking them into certain packaging sizes.) Even when a consumer good such as paper towels can’t spoil, people with a small home might not have the space for a stockpile.

The bias against solo consumers runs deep: Recipes are rarely written for a single diner, and DePaulo said that she has heard from single people who have had trouble booking restaurant reservations for one. Also, some aspects of travel, particularly lodging, are much more expensive, per person, for single people. These all may seem like small annoyances, but in practice they are regular reminders that American society still assumes that the default adult has a partner and that the default household contains multiple people.

More concerning, some health-care protocols are essentially built on the assumption that a patient lives with someone who can support them. Certain medical procedures require patients to be dropped off or taken home by someone who could stay with them. A friend can fill this role for people who live alone, but they may not want to make a burdensome request or share sensitive information about their health. In the Facebook group that DePaulo created for single people, some members have reported paying a driver from a ride-hailing service extra to pose as a friend or just forgoing a procedure entirely.

And people who live alone don’t always get to take full advantage of government policies. For instance, the Family and Medical Leave Act, a (fairly meager) law that protects some workers’ jobs if they take unpaid leave to look after a loved one, covers care only for spouses, children, and parents. A person who lives alone and doesn’t have a spouse might want to look after a sibling or close friend, but the law doesn’t cover that.

According to the Pew Research Center, the share of American adults who aren’t married and don’t live with a romantic partner has also been growing, having jumped from 29 percent in 1990 to 38 percent in 2019. Many of these people live with others, such as their parents or other relatives, and some of these disadvantages apply to this group as well, depending on whom they share a home with. They may not be able to get a ride to the doctor from a homebound older relative, or may get treated differently at work if they don’t have a child. Some of them might want to live alone, but can’t afford to do so.

And many single people, whether they live alone or with others, constantly face the stigma associated with not being partnered. “It’s oppressive, always getting pitied,” DePaulo said. “People have bought into the ideology that having someone is better—[that] the more natural, normal, superior way of being is being coupled or having a family.”

She sees this norm in the political rhetoric around virtuous, “hardworking families,” and thinks that this cultural default can to some extent be blamed for the ways in which American society has been slow to adapt to people who are single or live alone. She also attributes the slowness to “cultural lag”: In the future, lots of Americans are going to live alone—tens of millions already do—and eventually, society will, with hope, catch up.

The Economist Espresso via e-mail for Monday October 4th

Deep impact: it’s time to ditch the small talk

Imagine waiting in a queue or for a bus, when a stranger sidles up to you and genially asks: “What is your life’s greatest regret?” If that thought fills you with horror, read on. According to research in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, people secretly crave deeper conversations with strangers.

In experiments with 1,800 people, pairs of strangers were prompted to discuss topics either shallow (“Seen anything good on telly lately?”) or deep (“When was the last time you cried?”). Before-and-after surveys revealed that all conversations, but especially deeper ones, were less awkward than people expected. They were also more enjoyable and aroused a greater sense of connectedness than stock chit-chat.

Psychologists say people underestimate how interested in them strangers are, and should delve deeper than the usual natter about football or the weather. So the next time you break the ice with a stranger, consider using a sledgehammer instead of a pick.

Deep impact: it’s time to ditch the small talk PHOTO: GETTY IMAGES Imagine waiting in a queue or for a bus, when a stranger sidles up to you and genially asks: “What is your life’s greatest regret?” If that thought fills you with horror, read on. According to research in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, people secretly crave deeper conversations with strangers. In experiments with 1,800 people, pairs of strangers were prompted to discuss topics either shallow (“Seen anything good on telly lately?”) or deep (“When was the last time you cried?”). Before-and-after surveys revealed that all conversations, but especially deeper ones, were less awkward than people expected. They were also more enjoyable and aroused a greater sense of connectedness than stock chit-chat. Psychologists say people underestimate how interested in them strangers are, and should delve deeper than the usual natter about football or the weather. So the next time you break the ice with a stranger, consider using a sledgehammer instead of a pick.

Daily briefing | The Economist

Memory and the Holocaust in Ukraine A bold, controversial memorial to a wartime massacre in Kyiv The mix of painful history, Russian involvement and oligarchs is explosive

A bold, controversial memorial to a wartime massacre in Kyiv | The Economist

Memory and the Holocaust in Ukraine

A bold, controversial memorial to a wartime massacre in Kyiv

The mix of painful history, Russian involvement and oligarchs is explosive

Sep 18th 2021

KYIV

On a balmy September evening locals stroll in a leafy park in Kyiv. Parents push prams. Couples kiss. Young men perch on benches with cans of beer and shawarmas. Among the trees and promenaders stand slabs of granite the height of a person. Implanted in each is a peephole, like the lens of a camera. Peer into one of them, and you see a colour photograph taken on this spot 80 years ago: a ravine, scattered clothes, three German officers looking over the edge. This is Babyn Yar.

The picture was taken at the beginning of October 1941. A few days earlier, on September 29th and 30th, Nazi forces shot 33,771 of the city’s Jews in the ravine (a figure that excludes small children). It was the biggest such massacre of the second world war. Over the next two years, perhaps 100,000 more people were killed, dumped and burned in the same place, including Roma, communists, Ukrainian resistance fighters and patients of a nearby psychiatric hospital. But the slaughter in Nazi-occupied Kyiv began with Ukraine’s Jews; 1.5m had perished by 1945, a quarter of all victims of the Holocaust.

The tragedy of Babyn Yar was never forgotten. Yet as both a topographical feature and a site of mourning, it all but vanished from the map after the war. Now, an international team of artists, scholars, architects and philanthropists is transforming the landscape again, physically and emotionally. The photographs are a small part of a vast project that involves museums, art installations, books, education initiatives and films. Endorsed by Volodymyr Zelensky, the country’s president, it is funded by businessmen including Mikhail Fridman, a Ukrainian-born Russian tycoon, his associate German Khan, and Viktor Pinchuk, a Ukrainian oligarch.

The mix of painful history, Russian involvement and oligarchs is explosive in today’s Ukraine. But the memorial’s ramifications go wider. Many countries have mass graves, “but nobody wants to remember [the victims]”, says Patrick Desbois, a Roman Catholic priest and adviser to the project who spent years documenting the “Holocaust by bullets”. The new memorial, he says, is a message to mass-murderers everywhere: “We always come back.”

For decades Babyn Yar was a place not only of murder but of the physical suppression of memory, first by the retreating Nazis, who scrambled to conceal their crimes, then by the Soviets. Josef Stalin wanted to celebrate his triumph, not mourn tragedy; after the war he launched a new anti-Semitic campaign of his own. Official historiography depersonalised the victims of Nazism as undifferentiated Soviet citizens.

Babyn Yar was levelled. In 1952 some of its cavities were flooded with pulp from a brick factory. There were plans to build a football stadium and entertainment park on top of it. The ravine did not go quietly: in 1961 a dam securing the pulp gave way and a mudslide carrying human remains hit a residential neighbourhood. Hundreds died (the exact toll was hushed up).

Later in the 1960s Viktor Nekrasov, a Kyiv-born Russian writer who had fought at Stalingrad and wrote about it movingly, spoke up about Babyn Yar. To him, covering up the Nazi genocide made the Soviet government complicit. Of the murder and “the subsequent attempt to forget about this murder, to eradicate the very memory of it”, he wrote in 1966, “the first is more tragic. The second is more shameful.”

Nekrasov led one of the first big commemorations of the massacre. Mourners, many of whom had known the victims, gathered at the edge of a Jewish cemetery that had been vandalised by both the Nazis and the Soviets. They held flowers and cried. The kgb cringed. The crowd was quickly dispersed; Nekrasov was expelled from the Communist Party and forced to emigrate. Then, in the early 1970s, Babyn Yar became a rallying point for Jewish dissidents. The Soviet authorities finally put up a monument near the site of the ravine, dedicated “to the Soviet citizens, prisoners and officers executed by the German occupiers”. There was no mention of Jews.

Murder and memory

If Soviet ideology had little room for the Holocaust, it has been a sensitive subject for some Ukrainians for other reasons. Millions of them fought in the Red Army; millions died, in and out of uniform. But in some places the Nazi slaughter was abetted by Ukrainian auxiliary policemen. In others Jews were slain by nationalist partisans. (In the 1960s Ivan Dziuba, a non-Jewish poet who spoke of his shame over anti-Semitism in Ukraine, was imprisoned.)

After the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991 and Ukraine won independence, the area that had been Babyn Yar became a park. A jumble of plaques and memorials were erected; politicians paid their respects. But the main theme of historical restitution was the Holodomor—the famine Stalin inflicted on Ukraine in the 1930s, killing millions of peasants. As historical trauma often is in new states, the Holodomor became a central plank of national identity.

Five years ago Mr Fridman, the tycoon, saw an opportunity. Born in 1964, he grew up in Lviv, a city in western Ukraine where the large pre-war Jewish population had been all but obliterated. As a student in the 1980s he moved to Moscow and became one of Russia’s richest businessmen. After the revolution that overthrew Ukraine’s Kremlin-backed government in 2014, business and civil society helped fill a void left by the state’s confusion. Having made his fortune in the turbulence that followed the Soviet collapse, Mr Fridman knew that such moments should be seized.

In 2016 he assembled a coalition of businessmen, politicians, activists and intellectuals, both Jewish and gentile, and launched the Babyn Yar Holocaust Memorial Centre. “Private money frees the project from state ideology,” Mr Fridman says.

How to remember the second world war is always a neuralgic subject. In Poland, references to Polish complicity in Nazi atrocities can result in legal action; in Russia, comparison between Stalinism and Nazism is now a crime. And the idea of private cash shaping memory of the conflict, and of the Holocaust, would be jarring anywhere. Given Russia’s annexation of Crimea and the war in the Donbas—not to mention Kremlin propaganda that tars Ukrainians as fascist—the involvement of Russian citizens at Babyn Yar inevitably riled politicians and others. Some feared that the Holodomor would be downplayed. Petro Poroshenko, who as president until 2019 supported the initiative, now worries that representatives of Russia are using history to “discredit the Ukrainian state and Ukrainians”. Some local Jewish activists were irked by the outsiders too.

The appointment in 2019 of Ilya Khrzhanovsky, a Russian film director, as the project’s artistic overseer led to more controversy. His previous work includes a dark film installation exploring coercion and power in a Soviet physics institute, which caused scandals in Ukraine and elsewhere. Mr Fridman has been accused of nefarious meddling; Mr Khrzhanovsky’s initial ideas, such as a suggestion of role-playing by visitors as victims and killers, led to charges that he was planning a sort of Holocaust theme park.

The role-playing was dropped—but Mr Khrzhanovsky is determined to make an emotional impact on an audience for which the war is no longer part of living memory. Anton Drobovych, who left the project and now leads the Ukrainian Institute of National Remembrance, a state body, is sceptical about both the approach and what he sees as the aloof way it has been implemented. “You can’t build a memorial of such national and international significance,” he thinks, “without a proper dialogue and consultation with society.”

The work is ongoing. Four museums, tackling different aspects of Babyn Yar’s history, are still to be built. But Mr Fridman, whose outlook is shaped as much by his Jewish roots and upbringing in Ukraine as by his affiliation to Russia, does not see the memorial as a way to attribute blame; for him it is a means to empower Ukrainian society. “The ability of a country to talk about its past is a sign of maturity,” Mr Fridman says. “People who assume the role of victim can rarely achieve success.”

Sergei Loznitsa, an unflinching Ukrainian film-maker, agrees. “Telling the truth about the Holocaust is intertwined with state-building in Ukraine and the forging of its national identity,” he says. His dispassionate documentary, “Babyn Yar. Context”, which was partly funded by the memorial project, had its premiere at this year’s Cannes film festival, to great acclaim. Based on German and Soviet archive footage, it shows devastated Soviet soldiers surrendering to German troops; Jews being abused by their neighbours in Lviv; jubilant crowds tearing down Stalin’s portraits and cheering the Nazis as liberators, and less jubilant crowds greeting Soviet soldiers a few years later.

The massacre at Babyn Yar was not filmed. Instead viewers see pictures of Kyiv’s Jews and a long, scrolling tribute from “Ukraine without Jews”, an essay by Vasily Grossman, a Soviet war correspondent and author of the epic novel “Life and Fate”, whose mother died in the Holocaust:

Stillness. Silence. A people has been murdered. Murdered are elderly artisans…murdered are teachers, dressmakers; murdered are grandmothers who could mend stockings and bake delicious bread…and murdered are grandmothers who didn’t know how to do anything except love their children and grandchildren…This is the death of a people who had lived beside Ukrainian people for centuries, labouring, sinning, performing acts of kindness, and dying alongside them on one and the same earth.

Grossman’s essay (translated by Polly Zavadivker) captures the ultimate purpose of the memorial as Mr Khrzhanovsky sees it: to rescue faces and voices from oblivion; to make them real, so they can be remembered, mourned and loved for who they were. “We want it to be a place of living memory and of empathy, where people—whatever their age or nationality—can establish their own emotional connection with those who died here. And you can only feel empathy for concrete people.”

He began by collecting names and scanning archives to construct biographies of victims and perpetrators. A team of forensic architects and historians studied old maps, soil samples, photographs and witness statements to reconstruct the lost topography, and the terrible events that followed the Nazi invasion. The information has been used to produce a3d model depicting scenes, buildings and people, which will be encased in a huge kurgan, or burial mound, erected on what was the edge of the ravine. The more detailed and tangible the story of Babyn Yar, the more universal its meaning is intended to be.

The life that was

Among the first art installations to be unveiled was a “mirror field”, designed by Maksym Demydenko and Denis Shibanov. A large stainless-steel disk covers the ground, from which rise ten vertical columns, shot through with bullets of the same calibre used by the Nazis in 1941 (see lead picture). Visitors see their own reflections in the perforated columns and are immersed in sounds that emanate from below—names, prayers and snippets of everyday life recorded in Kyiv before the war. When night falls, the field becomes a mirage of this extinguished life.

A path leads to the “crying wall” (pictured), created by Marina Abramovic, a feted Serbian artist, which will be completed before a state memorial service on October 6th. A 40-metre-long wall, made of Ukrainian coal, is embossed at the level of the head, heart and stomach with quartz crystals, meant to reflect the diversity of victims at Babyn Yar. Water weeps out. Nearby is a symbolic synagogue, designed by Manuel Herz, a Basel-based architect, made from Ukrainian oak and partly open to the elements. Once again, the past is present: the interior is decorated with copies of ornaments from long-gone synagogues in western Ukraine.

“Memory is not the past. It is the consequence of the past, it is what makes present life possible,” says Anna Kamyshan, who grew up in Ukraine and helped develop the project. Some of her forebears died in the Holocaust; others cheered the murderers. What defines her identity, she says, “is not my blood, but this landscape, this environment, this soil. This Babyn Yar.” ■

This article appeared in the Books & arts section of the print edition under the headline “The ravine”